Non-deposit products are: not insured by the FDIC;

are not deposits; and may lose value.

Written by: Rodney Hathaway, Chief Investment Officer

In recent months, we’ve received numerous questions from clients about tariffs, particularly as the current presidential administration has brought the issue back into the spotlight. Rather than tracking every tariff announcement, let’s take a broader look at the history of tariffs in the U.S. and their long-term implications.

The History of Tariffs in the U.S.

Tariffs have played a pivotal role in U.S. trade policy for much of our nation’s history. One of the first significant laws passed after the nation’s founding was the Tariff Act of 1789, championed by Alexander Hamilton. This legislation aimed to protect the fledgling U.S. manufacturing sector, and tariffs became a critical source of revenue for the federal government, especially through the Civil War period when they accounted for about 90% of federal income.

Throughout the 19th century, the U.S. imposed an average tariff of around 20%. However, after the Civil War, tariffs increased to about 50%. By the early 20th century, with the introduction of the income tax in 1913, tariffs as a revenue source began to decline.

For most of the 20th century, economic theory shifted toward the idea of competitive advantage — the belief that countries should focus on producing what they do best and trade with others for the rest. By the 1950s, American companies were seen as competitive on the world stage, and tariffs largely fell out of favor after World War II.

China’s Entry into the World Trade Organization

The landscape shifted dramatically in 2001 when China was admitted to the World Trade Organization (WTO) under President Bill Clinton. This was a pivotal moment in global trade, as China agreed to reduce tariffs and uphold intellectual property rights as part of its WTO membership.

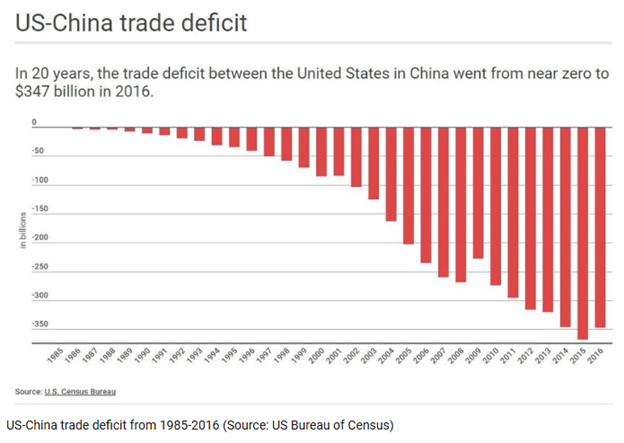

Before China’s WTO accession, tariffs between the U.S. and China were relatively low — China had an 8% tariff on U.S. goods, while the U.S. had only a 3% tariff on Chinese goods. However, after China’s entry into the WTO, the U.S. trade deficit with China grew significantly, peaking at $418 billion in 2018.

The Pros and Cons of China’s WTO Membership

Over the past 25 years, the results of China’s WTO membership have been mixed:

The Benefits:

- Lower Prices for Consumers: American consumers have enjoyed access to cheaper Chinese goods.

- Market Access: Some American companies have benefited from selling products in China’s massive market.

- Poverty Reduction in China: Hundreds of millions of Chinese citizens have lifted themselves out of poverty by joining the industrial revolution.

The Drawbacks:

- Environmental Concerns: China’s manufacturing practices have often skirted WTO regulations, contributing to global pollution.

- Intellectual Property Theft: U.S. and European companies have lost significant intellectual property to Chinese competitors.

- Trade Deficit: The U.S. has faced a consistent trade deficit with China, which has ranged from $300 billion to $400 billion per year.

- Job Losses: Since 2000, the U.S. has lost approximately 4 million manufacturing jobs to China.

Trump’s Tariff Policy: A Long-Term Strategy

In 2017, President Trump implemented tariffs on Chinese goods in an attempt to reverse the economic damage caused by this trade imbalance. While tariffs inevitably cause short-term pain — such as higher prices for consumers — the long-term strategy is focused on rebuilding America’s manufacturing base and reducing reliance on foreign production.

Consider this: the 4 million manufacturing jobs lost to China represent approximately $250 billion in lost wages annually for American workers. This shift in wealth has had a devastating impact on middle-class America. Trump’s tariff policy aims to reverse that trend by bringing manufacturing jobs back to the U.S.

The Example of Honda’s Investment in Indiana

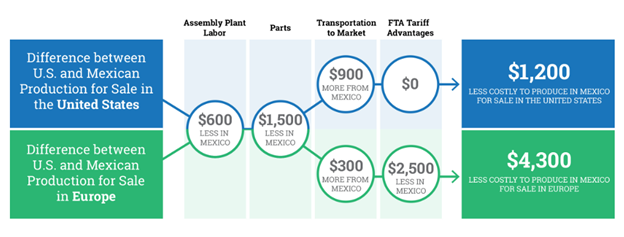

A recent example illustrates how tariffs could play a role in reshoring jobs: Honda’s decision to build 210,000 Civic Hybrids annually in Indiana starting in 2027. Initially, Honda had planned to produce these cars in Mexico, but the current tariff policies influenced their decision to bring production back to the U.S.

While manufacturing in Indiana is more expensive than in Mexico — approximately $1,200 more per car — the creation of good-paying manufacturing jobs far outweighs this additional cost. A plant producing 200,000 cars annually would need to hire around 10,000 workers, with an average wage of $60,000 per year. This represents an annual economic value of $600 million in wages, compared to the $250 million added cost due to higher manufacturing expenses in Indiana. The net result is a $350 million economic gain.

Center for Automotive Research. (2017, January 17). The move to assemble vehicles in Mexico is about more than low wages. Center for Automotive Research. https://www.cargroup.org/the-move-to-assemble-vehicles-in-mexico-is-about-more-than-low-wages/

The Road Ahead: Restoring Manufacturing Jobs

The potential for restoring even a portion of the 4 million jobs lost to China could have a significant positive impact on the U.S. economy. If we were to reshore 2 million jobs — half of the total lost — it could add $120 billion per year to the economy in terms of worker income. In a best-case scenario, restoring all 4 million jobs could not only eliminate the U.S. trade deficit with China but also strengthen the domestic economy in the long term.

While the current tariff negotiations have caused volatility in the stock market, the broader strategy behind these policies is aimed at making the U.S. economy more resilient and less dependent on cheap foreign goods.

A Balanced Perspective

In the short term, American consumers may feel the impact of higher prices on imported goods. However, the potential long-term benefits — from job creation to a stronger manufacturing sector — could be substantial. For decades, the U.S. has enjoyed the benefits of low-cost Chinese goods, but this has come at the expense of millions of good-paying American jobs.

It’s clear that the road to restoring America’s manufacturing base will require some short-term sacrifices. But if successful, these policies could strengthen the middle class and bring a more sustainable, balanced economy to the U.S. for years to come.